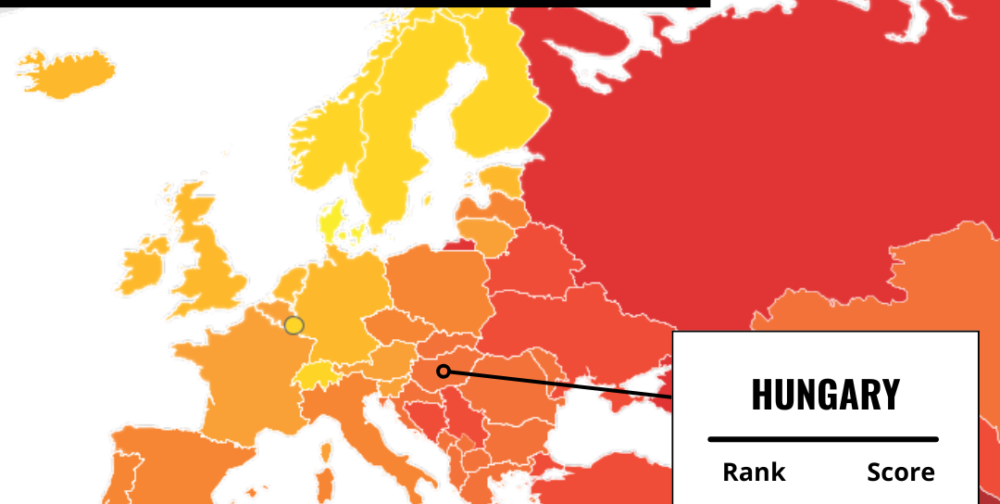

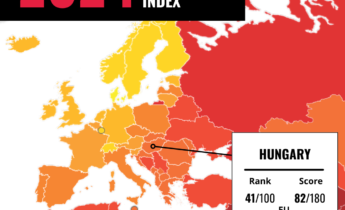

For the third year in a row, Hungary retained its ranking as the European Union’s (EU) most corrupt country in the 2024 edition of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published today by the Berlin-based Secretariat of Transparency International (TI). The CPI, which is compiled every year by the international anti-corruption organisation, also shows that Hungary’s ranking on an international scale of 180 countries fell by six places to the 82nd within a year. In the absence of sufficient measures to restore the rule of law and to weed out systemic corruption in Hungary, the country irrevocably lost 1.04 billion euros worth of EU cohesion policy funding in 2024, and more losses are to be expected in the coming years, according to TI Hungary’s country report released in Budapest on 11 February.

Today’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is the 30th published by the Berlin-based Secretariat of Transparency International (TI-S). It ranks countries based on the resilience of their public sector against corruption. Hungary received 41 points for its 2024 performance on a 100-point scale where 0 marks the highest level, and 100 the lowest level of perceived corruption. This is one point less than in 2023, and it puts Hungary in 82nd place among 180 countries assessed worldwide, a significant drop from its 76th place in 2023. With 55 points, Hungary ranked 46th in 2012, which means that over the past 12 years, the country’s ranking fell by 14 points and 36 places on the CPI scaling.

For the third year in a row, Hungary finished last place in the EU and its score fell the most, by 14 points. In 2014, Hungary finished 21st in the then 28-member EU. In 2020, Hungary shared the last place in the EU with Bulgaria and Romania, only to be outperformed in later years first by Romania and then by Bulgaria.

The performance of Central and Eastern European EU countries varies greatly: the difference between the best- and the worst-performer – Estonia and Hungary, respectively – has grown to 35 points. The Visegrad4 countries – except for Hungary – are middle-ranking in comparison to other EU member states. Slovakia’s ranking fell by 5 points and 12 places compared to 2023, which – along with Malta’s performance – was the biggest drop in the EU in 2024. This may have to do with the change of government in Slovakia after the 2024 general elections, which brought a populist government with little respect for the rule of law to power.

Overall, the 2024 CPI results show that in 16 of the 27 EU countries the resilience against corruption has declined compared to 2023. “Corruption is an evolving global threat that does far more than undermine development – it is a key cause of declining democracy, instability and human rights violations,” said François Valérian, chair of Transparency International. “The international community and every nation must make tackling corruption a top and long-term priority. This is crucial to pushing back against authoritarianism and securing a peaceful, free and sustainable world,” he said.

EU funding and the rule of law

For the first time in the history of the EU, Hungary – due to systemic corruption and rule of law problems – irrevocably lost 1.04 billion euros worth of cohesion policy funding in 2024. With this, the country’s 2021-2027 EU cohesion policy budget has shrunk to 20.7 billion euros. The legal basis for partially depriving Hungary of its cohesion policy budget is the 2020 EU conditionality regulation, which details possible actions by EU institutions in cases when corruption and rule of law deficiencies in a member state jeopardise the transparent and efficient spending of EU money. Hungary is also at risk of losing 10.4 billion euros, the country’s share of the EU’s post-COVID-19 Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). So far, Hungary has been denied RRF funding due to corruption and rule of law problems. If Hungary fails to fulfil all 27 measures that are pre-requisites for accessing the RRF money, or it fails to complete all RRF-funded projects by the end of 2026, it may lose its entire RRF share.

Under pressure from the conditionality procedures, a package of reforms adopted in Hungary in the fall of 2022 introduced the strongest anti-corruption measures ever seen from the governing elite (which is commonly referred to in Hungary as the “System of National Cooperation” – NER). After two years, however, it is clear that these reforms were not sufficient to dismantle systemic corruption, mainly because the Hungarian government in several cases sabotaged the implementation of measures prescribed in the EU conditionality procedure. The creation of the Integrity Authority and the Anti-Corruption Task Force – a consultative body helping the work of the Authority – has been a half-solution, and the asset declaration system remains totally inadequate for scrutinising the enrichment of politicians.

Some other elements of the 2022 reform package are insufficient because the measures requested by the EU did not go far enough to weed out corruption even if they were to be fully implemented. This has been the case with the “public interest asset management foundations” (“KEKVAs”) – one of the most innovative instruments invented by the NER for pumping public money into private pockets –, the judicial and the criminal procedure reforms, and the accessibility of data of public interest.

TI Hungary also finds that the 2023 sovereignty protection act constitutes a severe violation of the rule of law. The Sovereignty Protection Office (SPO), established to enforce the sovereignty protection law, has extensive powers to investigate “anyone” and “anything”. TI Hungary was the first target of the SPO, which, in the summer of 2024, formally notified our organisation about “initiating a specific – and comprehensive – investigation” into our activities. The biggest problem with the sovereignty protection act is that it violates fundamental rights such as the right to freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial and the right to an effective legal remedy. But Hungary’s Constitutional Court has rejected the constitutional complaint of TI Hungary, so we will continue the case against the SPO at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Public procurement and other forms of re-distributing public money

Many of the commitments made by the Hungarian government in the national RRF implementation plan and within the framework of the EU conditionality procedure aim to improve transparency in public procurement, which in 2024 accounted for 4.6 percent of the GDP. However, the measures implemented so far have not triggered major changes in Hungary’s public

procurement system. For example, Hungary has committed to cutting back the number of single bid tenders. While the target has been achieved in the case of EU-funded public procurement procedures (where the share of single bid tenders has gone down to 5.5 percent), Hungary failed the 24 percent target set for 2023 for nationally funded tenders, and the 15 percent target set for 2026 seems an even harder nut to crack.

The high concentration in public tendering clearly indicates that the government’s action plan for boosting competition in public procurement and tackling systemic problems has not been successful, either. The excessive use of concession contracts and framework agreements has also contributed to market concentration in some segments. In the latter category, a limited group of companies tend to pocket all the hefty contracts with centralized top government agencies. The transparency of public procurement data is undermined by multi-level procedures and the use of special websites to publish data.

Various corporate and investment schemes that hide the identity of ultimate owners have become very popular in Hungary. These include the mushrooming private equity funds, and trust funds. Besides, preference shares whose owners are priority recipients of dividends are also widespread. Private equity funds have played a key role in channelling public money into private pockets by allowing public bodies to invest in the funds of privately held fund management companies.

Vicious circle of corruption and deteriorating economic output

“Recent socio-economic indicators show that Hungary has been trapped in a vicious circle since the Covid-19 pandemic: corruption has been undermining the country’s economic output,” said József Péter Martin, executive director of TI Hungary. He added that both in terms of corruption and economic output, the situation has deteriorated over the past five years.

As in previous years, the 2024 report finds a strong correlation between European Union member countries’ economic growth – measured by the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) – and their CPI ranking. Hungary is the EU’s most corrupt country with a humble economic output. The latest Eurostat figures (from 2023) paint a gloomy picture about the country’s economic performance. The per capita GDP in Hungary is at 77 percent of the EU average, matching the performance of Poland and surpassing only Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. The situation is even worse when it comes to household consumption: personal incomes in Hungary are the lowest in the EU. Further aggravating the situation is the fact that Hungary’s productivity has been low, and the development of human infrastructure (healthcare, education) has been neglected for many years. The volume of capital investments has also plummeted during the past two years, with foreign direct investments (FDI) hitting an all-time low in 2023.

The declining trends in the past five years can be traced back to two main, chiefly interlinked causes. After 2016, a series of poor economic policy decisions wrecked the Hungarian economy. For almost a decade, budgetary policy has disregarded the requirements for fiscal balance, and the monetary policy was characterized by the same mistake, although this was corrected by the National Bank of Hungary as of 2022. The other factor is systemic corruption, coupled with state capture, whereby important public institutions are serving private interests.

2024 was not without high-profile corruption cases. TI Hungary’s annual corruption report highlights three cases: multi-billion-forint real estate developments by investors linked to the government and Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party, 35-year concession contracts for highway and waste management, and canopy walkways with no trees in their vicinity.

***

About the Corruption Perception Index

The Corruption Perceptions Index scores 180 countries and territories around the world based on perceptions of public sector corruption, using 13 different data sources from 12 different institutions, including the World Bank, World Economic Forum, private risk and consulting companies, think tanks and others. The scores reflect the views of experts and businesspeople on numerous corrupt behaviours in the public sector, including bribery, state capture, nepotism in the civil service, and diversion of public funds. The data points are converted to a scale of 0-100 where 0 represents the highest level of perceived corruption, and 100 the lowest level of perceived corruption. The detailed description of the methodology can be found at Transparency International’s website: https://www.transparency.org/en/news/how-cpi-scores-are-calculated